sabato 27 febbraio 2021

lunedì 22 febbraio 2021

Accountants Have Learned To Live With Crypto...

Accountants Have Learned To Live With Crypto

Accounting standards developed for the 20th century are not equipped to deal with 21st century crypto assets. Assuming otherwise creates inaccurate and diminished financial reporting.

Recent headlines by the likes of Tesla, Microstrategy, and BNY Mellon, as well as statements by market titans such as Ray Dalio and Jeff Gundlach illustrate one consistent point; crypto is part of the mainstream financial conversation.

Bitcoin especially has come a long way from its early days as a cypherpunk-themed movement to create an alternative financial and payment system. In the context of 2021, bitcoin and other crypto are actually starting to become somewhat boring; just another asset class and investment opportunity for institutional investors, financial institutions, and retail investors alike versus a world changing idea.

If the story ended there, well, it would all sound pretty mundane. Unfortunately, that is only the surface, and these headlines obscure an extremely important problem that remains unaddressed; the accounting for crypto as it currently stands makes no business sense. That’s right, something as under-the-radar as accounting standards are quickly becoming a significant issue as crypto adoption and investment accelerates.

Let’s dig in.

The Problem

There is currently no widely accepted authoritative accounting guidance for crypto. Certain specific countries have implemented unique approaches that stand apart, but these are not widely adopted outside of these countries. In the accounting world, the two standard setting bodies are the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). It is true that the IASB has proven more flexible in terms of crypto accounting; there are no authoritative standards to that effect. In the US, and despite worthwhile efforts by the American Institute of CPAs (AICPA) to publish non-authoritative research, the FASB has so far refused to consider the issue of crypto-specific accounting guidance.

In the face of no authoritative standards, a consensus has developed that crypto should be treated as an indefinite lived intangible asset (like goodwill) for financial reporting purposes. At first glance this all seems fine since crypto is intangible and has no fixed expiration date. Peeling back the layers of this treatment, however, quickly reveals how inappropriate this classification is for crypto.

Following the rules of accounting for indefinite lived intangible assets, these assets are held on the balance sheet at the price paid for them (cost) less any impairment charges. Impairment, without getting overly technical, is a process by which assets are evaluated to see whether or not the book value is reflective of market value. If the market value has decreased, the asset is written down and an expense is recorded. Under US accounting standards, there is one other wrinkle to keep in mind; once an asset has been written down it cannot be written back up no matter what the market valuation becomes.

This accounting treatment might be fine for goodwill, an asset created due to paying more than the fair market valuation of an organization (think M&A) would imply, but does not work for crypto. Under this current treatment, any organization that invests in crypto will have to record this investment at cost, and mark it down whenever conditions trigger an impairment test, and would never be able to mark this asset back up.

Crypto is still a volatile market, and even just in 2021 there have been double-digit percentage swings in prices for bitcoin and innumerable other crypto. Treating crypto as the current consensus would indicate creates a situation where economic realities are not accurately represented.

[This blogger note: The same should be true for banking money. Once the people understand it is just an accounting fraud, the net value will go to zero...]

Think about it, is any other widely traded and free-floating

commodity or equity-like instrument treated this way? No. Why? Because

it does not make business sense and diminishes the usability of

financial reporting.

Potential Solutions

There are two possible solutions that could ultimately be implemented given the rapid proliferation of crypto on corporate balance sheets. Again, there is no widely implemented crypto-specific guidance, and these approaches do not align with current market consensus.

Option #1 is the simplest approach, and would involve choosing to treat, record, and report crypto investments as a commodity-like instrument. This would allow the changes in market value to be reported as they occur on the balance sheet, and be reported on the income statement (or through other comprehensive income). Implementing this approach, modifying existing standards to reflect an emerging asset class, would increase the transparency and usability of financial reporting.

A second option, and one that in a perfect world would already be in the pipeline at standard setters, is the development of entirely new standards for this entirely new asset class. Obviously this would take more time, require more input, and necessitate high levels of collaboration, but the following framework might make sense. Classifying different crypto depending on use case (currency alternative, commodity equivalent, or equity-like instrument) would allow new and more nuanced standards to enter the marketplace.

As far fetched as this might seem, a similar attempt was made to improve crypto reporting via the proposed (not passed) Token Taxonomy Act of 2019; a refreshing attempt by policymakers to encourage innovation and adoption of new technologies.

Takeaway

Crypto has rapidly moved from a fringe topic, to a relatively minor investment selection, to an investment being adopted by some of the largest corporations and asset managers in the world. This is fantastic news for wider adoption, but the accounting simply has not kept pace. Accounting professionals need to learn to live and work with crypto, and standard setters need to be proactive in the creation of crypto-specific standards. Applying standards developed for the 20th century economy to 21st crypto assets is already causing issues, and should be rectified to avoid wider market disruptions.

Sean Stein Smith

Sean Stein Smith is a Visiting Research Fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research, focusing on blockchain, cryptoassets, and the economic impact of these technologies. He is an Assistant Professor at the City University of New York (Lehman College), serves on the Advisory Board of Wall Street Blockchain Alliance, where he also chairs the Accounting Working Group, and chairs the Emerging Technology Interest Group of the New Jersey Society of CPAs. His research has been quoted in dozens of scholarly and practitioner publications, and he is a regular speaker at accounting and technology conferences. Follow him on Twitter.

venerdì 12 febbraio 2021

HISTORY OF INVENTION: ITALIAN BOOK-KEEPING "Doppia Scrittura"

Beckmann (Johann). A History of Inventions and Discoveries. J. Bell, 1797

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b792561&view=1up&seq=19

HISTORY OF INVENTIONS

ITALIAN BOOK-KEEPING.

THOSE who are acquainted with the Italian method of book-keeping must allow that it is an ingenious invention; of great utility to men in business; and that it has contributed to extend commerce and to facilitate its operations. It requires little less attention, reflection and accuracy, than many works which are styled learned; but it is undoubtedly true that most mercantile people, without knowing the grounds of the rules on which they proceed, conduct their books in as mechanical a manner as many of the literati do their writings.

The name, Italian book-keeping, Doppia Scrittura, with several words employed in this branch of science and still retained in all languages, make it probable that it was invented by the Italians, and that other nations borrowed it, as well as various short methods of reckoning, from their mercantile houses, at the time when all the East India trade passed through Italy.

De la Porte says [1], "About the year 1495, brother Luke an Italian published a treatise of it in his own language. He is the oldest author I have seen upon the subject." Anderson, in his Historical and chronological deduction of the origin of commerce [2], gives the following account: “In all probability, this art of double-entry accounts had its rise, or at least its revival, amongst the mercantile cities of Italy: possibly it might be first known at Venice, about the time that numeral algebra was taught there; from the principles of which science double-entry, or what we call merchants accounts, seems to have been deduced. It is said that Lucas de Burgo, a friar, was the first European author who published his algebraic work at Venice, anno 1494."

This author, who was one of the greatest mathematicians of the fifteenth century, and who is supposed to be the first person who acquired a knowledge of algebra from the writings of the Arabians, was called Lucas Paciolus, e Burgo S. Sepulchri, He was a Franciscan, and so surnamed from a town in the duchy of Urbino, on the Florentine confines, called Burgo S. Sepulchro [3].

Anderson tells us [4], that he had, in his possession, the oldest book published in England in which any account is given of the method of book-keeping by double-entry. It was printed at London, in 1569, in folio. The author, whose name is James Peele, says, in his preface, that he had instructed many, mercantile people in this art, which had been long practised in other countries, though in England it was then undoubtedly new. One may readily believe, that Mr. Anderson was not ignorant of the difference between the method of book-keeping by single, and that by double-entry; but he produces nothing to induce us to believe that Peele taught the latter, and not the former; for what he says of debit and credit is of no importance, as it may be applied also to the method by single-entry.

Of this Peele no mention is made in Ames' Typographical antiquities; bur in that work [5] there is an account of a still older treatise of book-keeping, entitled “A briefe instruction and manner how to keepe bookes of accompts, after the order of debitor and creditor, and as well for proper accompts, partible, &c. by three bookes, named the memoriall, journall, and ledger. Newly augmented and set forth by John Mellis schole maister. London 1588. 12mo.”

Mellis, in his preface, says that he is only the re-publisher of that treatise, which was before published at London in 1543 by a schoolmaster named Hugh Oldcastle. From the above title, and particularly from the three accompt books mentioned in it, I am inclined to believe that this work contained the true principles of book-keeping by double-entry.

The oldest German work on book-keeping by double-entry, with which I am at present acquainted, is one written by John Gotlieb, and printed at Nuremberg, by Frederick Peypus, in 1531 [6]. The author, in his preface, calls himself a citizen of Nuremberg, and says, that he means to give to the public a clear and intelligible method of book-keeping, such as was never before published. It appears, therefore, that he considered his book as the first of the kind ever published in Germany.

It is worthy of remark, that, even at the end of the sixteenth century, the Italian method of book-keeping began to be applied to finances and public accompts. In the works of the celebrated Simon Stevin [6b], published at Leyden in Dutch, and the same year in Latin, we find a system of book-keeping, as applied to finances, drawn up it appears for the use of Maurice prince of Orange. To this treatise is prefixed, in Dutch and Latin, a dedication to the duke of Sully, in which the author says, that his reason for dedicating the work to Sully was, because the French had paid the greatest attention to improve the method of keeping public accompts. The work begins with a conversation, which took place between Stevin and prince Maurice, respecting the application of book-keeping to public accompts, and in which he explains to the prince the principles of mercantile book-keeping.

This conversation commences with explaining the nature of debit and credit, and the principal accompts.

Then follow a short journal and ledger, in which occur only the most common transactions; and the whole concludes with an account of the other books necessary for regular book-keeping, and of the manner of balancing. Stevin expressly says, that prince Maurice, in the year 1604, caused the treasury accounts to be made out after the Italian method, by an experienced book-keeper, with the best success; but how long this regulation continued I have not been able to learn. Stevin supposes, in this system, three ministers, and three different accounts: a quaestor, who receives the revenues of the domains; an acceptor, who receives all the other revenues of the prince; and a thesaurarius (treasurer), who has the care of the expenditure. All inferior offices for receiving or disbursing are to send from their books monthly extracts, which are to be doubly entered in a principal ledger; so that it may be seen at all times, how much remains in the hands of each receiver, and how much each has to collect from the debtors. One cannot help admiring the ingenuity of the Latin translator [7], who has found out, or at least invented, words to express so many new terms unknown to the ancient Romans. The learned reader may, perhaps, not be displeased with the following specimen. Book-keeping is called apologistica or apologismus ; a book-keeper apologista; the ledger codex accepti expensique; the cash-book arcarii liber; the expence book impensarum liber; the waste-book liber deletitius; accounts are called nomina; stock account sors; profit and loss account lucri damnique ratiocinium, contentio or fortium comparatio; the final balance epilogismus; the chamber of accounts, or counting. house, logisterium, &c.

In the end of this work Stevin endeavours to shew that the Romans,, or rather the Grecians (for the former knew scarcely any thing but what the latter had discovered), were, in some measure, acquainted with book-keeping, and supports his conjecture by quoting Cicero's oration for Roscius.

I confess that the following passage in Pliny, Fortunæ omnia expensa, huic omnia feruntur accepta, et in tota ratione mortalium sola utramque paginam facit [8], as well as the terms tabulæ accepti et expensi ; nomina transata in tabulas, seem to indicate that the Romans entered debit and credit in their books, on two different pages; but it appears to me not yet proved, and improbable, that they were acquainted with our scientific method of book-keeping; with the mode of opening various accompts; of comparing them together, and of bringing them to a final balance. As bills of exchange and insurance were not known in the commerce of the ancients, the business of merchants was not so intricate and complex, as to require such a variety of books and accounts as is necessary in that of the moderns.

Klipstein is of opinion that attempts were made in France to apply book-keeping, by double-entry, to the public accounts, under Henry IV, afterwards under Colbert, and again in the year 1716. That attempts were made, for this purpose, under Henry IV, he concludes from a work entitled An inquiry into the finances of France; but I do not know whether what the author says be sufficient to support this opinion.

Those who have paid attention to the subject of finances know that, for twenty or thirty years past, mercantile book-keeping has begun to be employed at Vienna, in order to facilitate the management of public accounts, which in latter times, and in large states, have been swelled to a prodigious extent. For this improvement we are indebted to several works, some of them expensive, intended as introductions to this subject.

One of these is by counsellor Puchberg, another by Mr. st. Julian, chaplain to the charity schools, and another by Adam Von Heidfeld [9]. Stevin's work before mentioned shews clearly that this improvement is not new; and seems to lessen what is said, in a work published in 1777 [10], that count Zinzendorf was the author or patron of that excellent invention, the application of the Italian method of book-keeping by double-entry to finances and public economy.

1. La science des négocians et teneurs de livres, Paris 1754. 8vo. p. 12.

2. Vol. i. p. 408

3. In Scriptores ordinis Minorum, quibus accessit syllabus eorum qui, ex codem ordine, pro fide Christi fortiter occubuerunt - Recensuit Fr. Lucas Waddingus, ejusdem instituti theologus, Romæ 1650, fol. a work reckoned by Beyer, Vogt, and others, among the very scarce books, is the following information, p. 238, respecting this author: “Lucas Paciolus e Burgo S. Sepulchri, prope fines Etruriæ, omnem pene mathematicæ disciplinæ Italica lingua complexus est; conscripsit enim De divina proportione compendium; De arithmetica ; De proportionibus et proportionalitalibus; opus egregium et eruditum, rudi tamen Minervâ, ad Guidobaldum Urbini ducem. De quinque corporibus regularibus; De majusculis alphabeti litreris pinyendis ; De corporum folidorum et vacuorum figuris, cum suis nomenclaturis. Excusa sunt Venetiis anno 1509. Transtulit Euclidem in linguam Italicam, et alia ejusdem scientiæ composuit opuscula.”

The same account is given in Bibliotheca Umbriæ, sive De scriptoribus Umbriæ, auctore Ludovico Jacobillo. Fulginiz 1658. 410. p. 180. The oldest works of this author, as mentioned in Origine e progressi della stampa, o sia dell'arte impressoria, e notizie dell'opere stampate dall'anno 1457 fino all'anno 1600. Bologna 1722. 4to. to the dedication of which is subscribed Pellegrino Antonio Orlandi, are Fr. Lucæ de Burgo S. Sepulchri Arithmetica et geometria, Italice; characteribus Goth. Ven. 1494. fol. Liber de algebra. Ven. 1494. This is the work quoted by Anderson. Those who are desirous of farther information respecting Lucas de Burgo, may consult Heilbronneri Historia matheseos universæ. Lipsiæ 1742. 4to. p. 520. Histoire des mathematiques, par M. Montucla, Paris 1758. 4to. t. i. p. 441-476. Histoire des progrès de l'esprit humain dans les sciences exactes, par Saverien. Paris 1766. 8vo. p. 18 et 38.

4. Vol. i. p. 409.

5. P. 410.

6. The whole title runs thus: Ein Teutsh verstendig Buchhalten fur herren oder gesellschafter inhalt wellischem process, des gleychen vorhin nie der jugent is furgetragen worden, noch in druck kummen, durch Joann Gotlieb begriffen und gestelt. Darzu etlich unterricht für die jugent und andere, wie die posten so auss teglichen handlung fiessen und furfallen, sollen im jornal nach kunstlicher und buchhaltischer art gemacht, eingeschrieben und nach malss zu buch gepracht werden. Cum gratia et privilegio. Laus Deo. [Una contabilità comprensibile in tedesco, per gentiluomini o azionisti, contenente il processo ondoso, la stessa non è mai stata eseguita in precedenza dai giovani, né è stata stampata, ora compresa e creata da Joann Gotlieb. Inoltre, una serie di lezioni per i giovani e altri, sul modo in cui gli oggetti scorrono e si avvicinano, dovrebbero essere tenuti nel diario in modo artificiale e contabile, inscritti e registrati su misura. Con grazia e privilegio. Lode al Signore.]

6b. See: Chatfield, Michael and Vangermeersch, Richard, "History of Accounting: An International Encyclopedia" (1996). Individual and Corporate Publications: "Stevin was one of the first authors to compose a treatise on governmental accounting. He did this in Vorstelicke Bouckbouding op de Italiaensche Wyse in 1604 (Flesher). This book included four parts: Commercial Bookkeeping; Bookkeeping for Domains; Bookkeeping for Royal Expenditures; and Bookkeeping for War and Other Extraordinary Finances. The book was written for Stevin's patron and friend, Prince Maurice of Nassau. Stevin stressed that the application of double entry for municipalities and governments was very much needed because supervision in municipalities and governments was weaker there than in businesses. Governmental treasurers often became rich, and the government poor on account because of the lack of a strong double entry control system. It is likely that Stevin also had an impact in Sweden as well as in the Netherlands. The Swedish government reorganized its accounting system and introduced double entry for its government in 1623. O. Ten Have (1956), head of the Department of Social and Economic Statistics, Netherlands Central Bureau of Statistics, traced Stevin's effect through the Dutch merchant, Abraham Cabeljau, who headed the Swedish efforts on double entry accounting. Stevin's works were collected in a massive two-volume set entitled Wisconstighe Ghedachtenissen (vol. 1, 1608 and vol. 2 in 1605) which was a collection of the manuscripts of the lessons given from Stevin to Prince Maurice. Stevin's bookkeeping text was included in the set. It is important to note for accounting education that Stevin used the form of a dialogue between himself and Prince Maurice for setting a systematic rationale for bookkeeping practices. The basis of bookkeeping, according to Stevin, is the beginning and the end of "property rights." This idea is a current topic, and there is rich "property rights" literature with emphasis on rights established by contracts. Stevin was one of the first accounting historians, and he made investigations into the antiquity of bookkeeping. Double entry accounting, he stated, has many roots in Roman (or even Greek) times. The importance of accounting history for the development of a sound and realistic accounting theory and a deeper understanding of the accounting heritage by accountants has recently been recognized. The accounting profession has evolved over many centuries. Stevin recognized, too, that book-keeping is first of all a way of sorting financial information, and his balance sheet compilation (staet proef) is carried out to ascertain mathematically the profit of the year. Stevin is considered to be the inventor of the income statement. "Stevin developed the income statement as proof of the accuracy of the change in owners' equity on the balance sheet" (Flesher). There is a great difference between Pacioli and Stevin, too. While Pacioli, for example, began the inventory: "In the name of God, November 8th, 1493, Venice," Stevin omitted all religious notations at the tops of pages or at the beginning of books. This is a fundamental point indeed. Perhaps this is one of the reasons that when in 1645 a proposal was made to erect a statue to this otherwise so illustrious native in Stevin's birthplace Bruges, there was much opposition from the local clergy to the plan. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/acct_corp/168/

7. Bayle says, that the Latin translation of Stevin's works was executed principally by Willebrord Snellius.

8. Lib. ii. Cap. 7.

9. A short account of this improvement, and the writings it gave rise to, may be found in Klipstein, Grundsasse der wissenschaft rechnungen einzurichten [Principles of scientific accounting to be established]. Leipzig 1778. 8vo. and also in another work, by the same author, entitled Grundsasse der rechnungswissenschaft auf das privater mogen angewendet [Basic principles of accounting applied to private life]. Wien 1774. fol.

10. Denkwurdigkeitenvon Wien 1777. 8vo. p. 210.

lunedì 8 febbraio 2021

Money creation, bank profits, and central bank digital currency

Money creation, bank profits, and central bank digital currency

Dirk Niepelt 05 February 2021

Source: https://voxeu.org/article/money-creation-bank-profits-and-central-bank-digital-currency

Banks create deposit money, which is a cheap source of funding because deposits serve as a means of payment whose liquidity compensates for yield (e.g. McLeay et al. 2014). Many commentators have reservations about such private money creation. They argue that private banks reap the benefits of publicly provided central bank money by leveraging deposit insurance and lender-of-last-resort guarantees. Others disagree and contend that banks themselves produce liquidity and add value.

Either way, it is natural to ask how much banks profit from the deposit liquidity spread. In a recent paper (Niepelt 2020c), I provide an answer by developing a method to quantify the funding cost reduction. I find that for the US, it is in the order of half a percent of GDP. This has important implications for the discussion about central bank digital currency because the deposit spread takes (or should take) centre stage in that discussion.

Central bank digital currency and bank funding

While more and more central banks examine the introduction of digital currencies, many governing boards are concerned about ‘bank disintermediation’.1 After all, the introduction of ’reserves for all’ would likely lead households and firms to convert some of their bank deposits into digital currency. But this would not imply a loss of bank funding, at least on impact. If a depositor transferred funds from her bank to the central bank, the latter would automatically refinance the former (by accepting the incoming payment). A central bank loan to the bank would ‘back’ the newly created central bank digital currency.2

The key question is at what interest would the central bank charge? If it charged an equivalent loan interest rate that replicated the bank’s deposit financing conditions, then central bank digital currency would leave the bank’s environment essentially unchanged.3

Funding cost reductions from money creation

I exploit this equivalence logic to quantify banks’ funding cost reduction due to money creation. The argument proceeds in three steps.

First, I derive a model-independent measure of the equivalent central bank loan rate. This rate renders a bank indifferent between deposit financing under the status quo, or the central bank loan in a world with central bank digital currencies:

- Under the status quo, the bank issues deposits at a (possibly set) deposit interest rate; invests a share in central bank reserves, which pay another rate; and invests the remainder in projects, which yield yet another rate of return. The bank may also bear operating costs for payment services which are connected to the bank’s deposit base.

- In the central bank digital currency world, customers convert some deposits into digital but a central bank loan replaces them (net of the share of deposits that was invested in reserves). Since the net costs of deposit funding reflect the interest rates on deposits and reserves, the reserves-to-deposits ratio, as well as the operating costs the equivalent central bank loan interest rate, depends on each of these factors as well.

Second, I compute by how much the bank funding rate would differ in the central bank digital currency world if the central bank charged the risk-free interest rate rather than the equivalent loan rate:

- The difference is simply the spread between the risk-free rate and the equivalent loan rate, and it reflects the profitability of private money creation. If the risk-free rate exceeds the equivalent loan rate then deposit funding is cheaper for banks than funding at the risk-free rate (due to deposits’ liquidity value for depositors).

Finally, I conclude that, relative to GDP, the funding cost reduction under the status quo that banks enjoy because they issue deposits rather than non-liquid liabilities equals the product of two terms:

- The spread between the risk-free rate and the equivalent loan rate discussed above.

- The GDP-share of banks’ net funding from money creation. That is, the GDP-share of deposits net of reserve holdings.

This funding cost reduction can be interpreted as an implicit subsidy for banks. After all, in the equivalent central bank digital currency world, it is solely the central bank which provides liquidity for households and firms, not commercial banks.

Large and volatile implicit bank subsidies

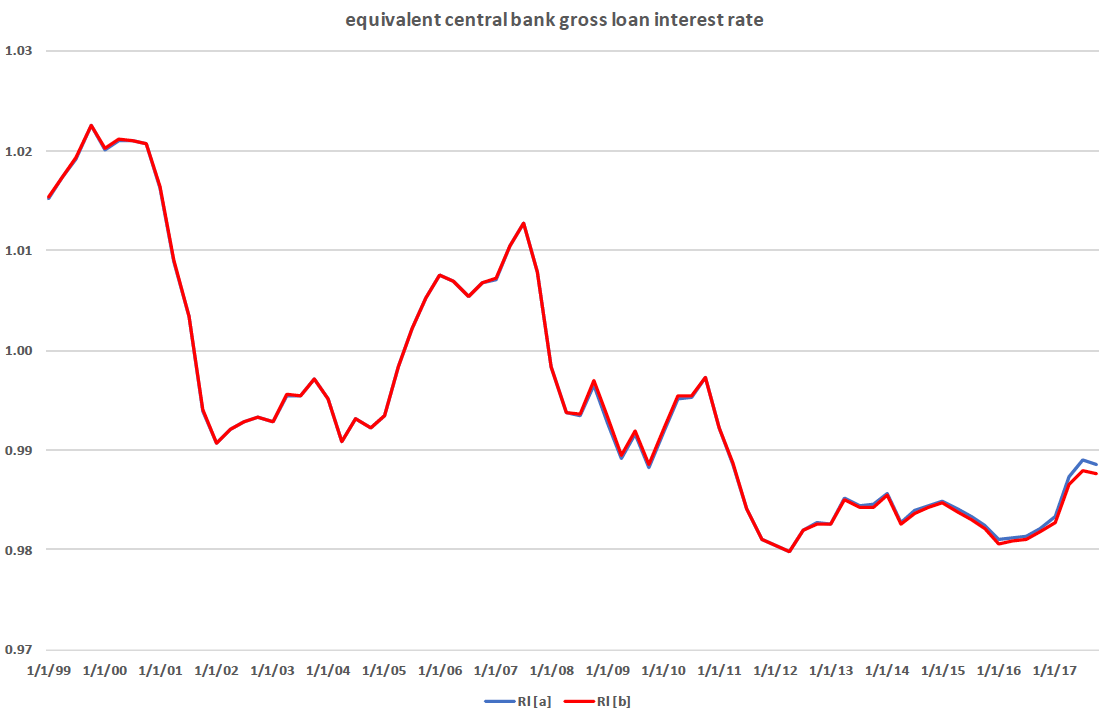

Figure 1 displays two estimates (reflecting alternative measures of deposits) of the equivalent central bank gross loan interest rate in the US during the period 1999—2017.4 Both series are inflation adjusted and constructed under the assumption that operating costs equal 1% (in line with estimates in existing research). That is, I posit that it costs banks 1% to operate payments associated with a dollar of deposit funding.

Figure 1

The figure shows that the equivalent loan rate falls from nearly 2% early in the sample to -0.5% towards the end, with a temporary increase to 1% in late 2010. We can distinguish four phases:5

- Prior to 2008, the reserves-to-deposits ratio is tiny and the equivalent loan rate follows the deposit rate as a result.

- In 2008, the reserves-to-deposits ratio increases substantially, and this pushes the equivalent loan rate up as well.6 One dollar of net funding now requires more than one dollar of deposits – since the deposit rate exceeds the interest rate on reserves, the equivalent loan rate rises.

- Between 2009 and 2015, the interest rates on reserves and deposits practically coincide. As a consequence, the equivalent loan rate follows the interest rate on reserves, plus a factor that reflects operating costs.

- Finally, after 2015 the deposit rate falls below the reserves rate and this contributes negatively to the equivalent loan rate.

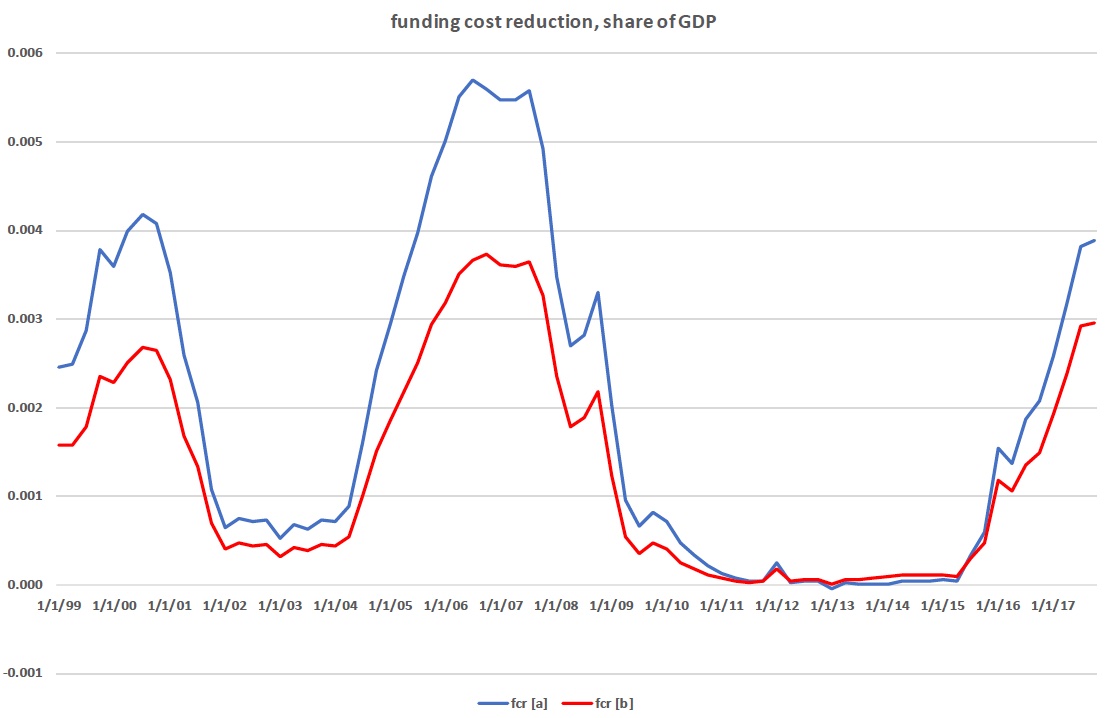

Figure 2 illustrates the implied funding cost reduction or implicit subsidy for banks. Again, the two series correspond to alternative measures of deposits. The time series fluctuate between 0.8% and -0.7% of GDP, reflecting two major drivers. On the one hand, it highlights a trend reduction in the risk-free interest rate relative to the equivalent loan rate, and fluctuations in the difference between the two rates. The trend effect reduces the profitability of private money creation. And on the other hand, there is the inverse-U shaped path of the reserves-to-deposits ratio after 2008 and an increasing deposits-to-GDP ratio.

Figure 2

Again, we can distinguish several phases:

- In the beginning of the sample, money creation by banks reduces their funding costs by roughly 0.5% of GDP (because the risk-free rate exceeds the cost of deposit funding). Equivalently, banks benefit from the equivalent central bank loan in the central bank digital currency world because the risk-free rate exceeds the equivalent loan rate.

- Between 2002 and 2004, the risk-free rate is lower and, as a consequence, the spread between the risk-free rate and the equivalent loan rate turns negative, as does the funding cost reduction.

- In 2005 and 2006, the risk-free interest rate rises again, pushing the spread and the funding cost reduction strongly back into positive territory where they remain until 2008.

- In early 2009, the interest rate spread turns negative and the funding cost reduction remains negative for eight years.

- Only in 2017 does the spread and the funding cost reduction become positive again, following a rise in the risk-free interest rate relative to the deposit rate and the equivalent loan rate.

Figures 3 and 4 are parallel to Figures 1 and 2. The only difference between the two pairs concerns the posited operating costs of depository institutions. Rather than assuming that payment operations cost banks 1% of their deposit volume, I now use a model to ‘back out’ operating costs, given banks’ choices of deposits and reserves holdings.

Figure 3 shows that the implied equivalent loan rate again displays a downward trend, falling by roughly three percentage points over the sample period, with a temporary reversal before the financial crisis (that is, earlier than under the previous calibration). The implied funding cost reduction varies between zero and 0.5% of GDP (Figure 4). It is positive at all times because in this setting the equivalent loan rate happens to always lie below the risk-free interest rate.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Conclusion

Either calibration implies that money creation substantially contributes to bank profits. Between 1999 and 2017 the funding cost reduction for US banks amounted to roughly 0.4 to 0.8% of GDP just before and around the financial crisis. In contrast, banks did not benefit from cost reductions (or they even bore additional funding costs) once financial markets had calmed. These numbers compare with NIPA data for financial sector profits on the order of 3% of GDP prior to the financial crisis, negative profits during the crisis, and 2-3% after the financial crisis.

In a world with full substitution of central bank digital currency for deposits, bank profits would have been the same as in the data had the Federal Reserve financed banks at the equivalent loan rate. Had the Federal Reserve refinanced banks at the risk-free interest rate instead, bank profits would have been substantially lower before, but not after, the financial crisis.

References

Auer, R, G Cornelli and J Frost (2020), “Rise of the central bank digital currencies: Drivers, approaches and technologies”, BIS working paper 880.

Brunnermeier, M K and D Niepelt (2019), “On the equivalence of private and public money”, Journal of Monetary Economics 106.

Kurlat, P (2019), “Deposit spreads and the welfare cost of inflation”, Journal of Monetary Economics 106.

Lucas, R E and J-P Nicolini (2015), “On the stability of money demand”, Journal of Monetary Economics 73.

McLeay, M, A Radia and R Thomas (2014), “Money creation in the modern economy”, Bank of England Quarterly Review, Q1.

Niepelt, D (2019), “Libra paves the way for central bank digital currency”, VoxEU.org, 12 September.

Niepelt, D (2020a), “Digital money and Central Bank Digital Currency: An executive summary for policymakers”, VoxEU.org, 3 February.

Niepelt, D (2020b), “Reserves for All? Central bank digital currency, deposits, and their (non)-equivalence”, International Journal of Central Banking 16(3).

Niepelt, D (2020c), “Monetary policy with reserves and CBDC: Optimality, equivalence, and politics”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15457.

Endnotes

1 See Auer et al. (2020) for an overview of CBDC projects. For a summary of pros and cons of CBDC and private sector alternatives, see Niepelt (2019, 2020a).

2 If the bank held reserves then its account at the central bank would be debited instead. The bank’s balance sheet would shorten but it would not suffer from a shortage of funds.

3 In fact, under broad conditions, CBDC would not have any macroeconomic consequences (Brunnermeier and Niepelt 2019, Niepelt 2020b, 2020c). If deposits are not collateralised, ‘neutrality’ requires the central bank loan to be uncollateralised as well.

4 I use FRED data for the interest rate on reserves; Kurlat’s (2019) estimates of the risk-free, “illiquid” interest rate and the deposit rate; and FRED data as well as data constructed by Lucas and Nicolini (2015) for reserves and deposits. Following Lucas and Nicolini (2015) I use two alternative measures for the deposit series: The sum of checkable and savings deposits, or the sum of checkable deposits and money market deposit accounts.

5 Simplifying a bit, the formula for the equivalent gross loan interest rate reads:

Rl = Rr + (Rn-Rr) / (1-z) + c / (1-z).

Here, Rl, Rr, and Rn

denote the gross interest rates on the central bank loan, reserves, and

deposits, respectively. c and z denote the unit operating cost and

reserves-to-deposits ratio, respectively.

6 The reserves-to-deposits ratio increases from a very low level (at which it had been since the early 1980s) to a maximum of 30% or 45%, depending on the deposit measure, in mid 2014. It reverts to 20% or 30% by the end of 2017.

lunedì 1 febbraio 2021

Banking cartel manipulating "free market" metal prices

Torgny Persson

Torgny Persson is the founder and CEO of BullionStar. In this blog,

Torgny shares what's happening inside BullionStar as well as news

and research from the local and global precious metals markets.

The silver short squeeze in physical silver at present is unprecedented. Even so, the spot price of paper silver is not even close to the real physical equilibrium price of silver. BullionStar may soon have no option but to abandon setting prices based on silver spot price altogether and move to fixed prices.

Thanks to r/WallStreetBets (WSB) and related spin offs, the wider public is starting to open its eyes to the corruption and cronyism in the financial markets including in the paper gold and paper silver markets.

For years, BullionStar has been one of the strongest critics of the manipulated precious metals markets where paper issuance of silver (out of thin air) exceeds the physical availability of real silver at a multiple of at least 100 to 1.

While some in the WSB movement have suggested purchases of SLV shares

and call options, many others are recommending physical silver. It’s

important to understand that purchases of SLV shares does not equate to

putting pressure on bullion banks. Bullion banks provide various

services to ETF’s, such as custodial services, and ETF’s are known for COLLUDING WITH CENTRAL BANKS.

This week may be the most interesting week for silver savers and investors in decades. The questions asked by this movement are of huge importance for the whole financial and monetary system.

– Is what we are seeing the start of a seminal silver crisis with the potential of finally bringing down the manipulated paper silver market?

– Can this movement lead to an attack of the very nature of unbacked fiat currency?

– Will the bullion banks try to smash the paper spot and paper futures prices back down and if so, will the price of physical silver definitively disconnect from the paper price?

– Can COMEX and SLV really source the physical silver required amidst the high demand?

Paper Silver Manipulation

What was claimed to be a conspiracy theory of bullion banks colluding to manipulate and suppress the paper price of precious metals have been proven true AGAIN and AGAIN.

BullionStar has also exposed, for example HERE, HERE, HERE, HERE, HERE and HERE how the precious metals industry organisations, like the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA), protect the interests of the paper dealing bullion banks rather than further the interest of physical producers and dealers.

Suppressing the paper price of gold and silver goes to the very core, not only of the financial system, but to the whole monetary system. In GOLD & SILVER PRICE MANIPULATION - THE GREATEST TRICK EVER PULLED, we wrote:

Manipulating gold and silver prices by spoofing futures trades and cancelling them is one thing. Central bank intervention into physical gold markets to dampen the gold price is another. But perhaps the most far reaching yet unappreciated method of manipulation is sitting there in plain sight, and that is the very structure of the contemporary ‘gold’ and ‘silver’ markets where PRICES ARE ESTABLISHED by trading in vast quantities of fractionally-backed synthetic gold and silver credit, be it in the form of vast quantities of UNALLOCATED POSITIONS that are ‘gold’ or ‘silver’ in name only, or in the form of gold and silver futures which haven’t the slightest connection with CME approved precious metals vaults and warehouses.

By siphoning off demand for real gold and silver and channeling it into unbacked or fractionally-backed credits and futures, the central banks and their bullion bank counterparts have done an amazing job in creating an entire market structure of futures and synthetics trading that is unconnected to the physical gold and silver markets. This structure siphons off demand away from the physical precious metals markets, and in doing so, creates a system of price discovery which is nothing to do with physical gold and silver supply and demand.

Apart from fractional-reserve banking, precious metals market structure is perhaps one of the biggest cons on the planet. So next time you think of precious metals manipulation, remember that in addition to spoofing and secretive central bank gold loans, the entire structure of the precious metals markets is unfortunately one big manipulation hiding in plain sight.

Silver Price Suppression

Another contributor to the suppression of the paper price for gold

and silver is the government manipulation of inflation figures.

Using ShadowStats Alternate CPI, THE REAL INFLATION-ADJUSTED ALL-TIME-HIGH FOR SILVER IS US$ 966.77. YES, NEARLY US$ 1,000 !

Following BullionStar’s post on the real inflation-adjusted ATH for silver, many followers of WSB has referenced to US$ 1,000 as the price target for silver. A ZEROHEDGE POST FROM TODAY with more than 2.1M views and 9K comments also makes reference to this price calculated by BullionStar while noting that the silver bullion market is one of the most manipulated on earth.It’s important for banks, central banks and governments to ensure that precious metals prices remain subdued. This is so because precious metals still indirectly backstops the whole monetary system. If the price of gold and silver were to skyrocket, it would expose that the emperor has no clothes, i.e. that fiat currency is intrinsically worthless.

Central banks and governments have employed a two pronged approach, where on one hand, the money supply is increased via Quantitative Easing to prop up bank and vested interests while on the other hand, the paper price of gold and silver is suppressed.

The QE DEFENDER GAME developed by BullionStar illustrates how central banks are propping up banks while suppressing gold and silver prices. GIVE THE GAME A GO AND SEE WHICH LEVEL YOU CAN REACH !

Play BullionStar’sQE DEFENDER GAMEthat illustrates how the central banks are propping up the banks while at the same time suppressing gold and silver prices.Physical gold and silver is measured in weight, has intrinsic value due to its metallic and monetary characteristics and IS MONEY IN THE TRUE SENSE. The currency of today is not backed by anything and has no monetary properties. Its value is dependent merely on a (false) perception of value. While BullionStar ACCEPT CRYPTOCURRENCY for order settlement of both buy and sell orders, cryptocurrency can not replace the age-old monetary properties of precious metals as the ultimate wealth asset.

BullionStar was one of the first bullion dealers in the world to ACCEPT BITCOINas payment for bullion back in 2014.Paper Silver Price vs. Physical Silver Price

Silver price discovery, which is how the price of silver is established by the market, is akin to a game of charades. Price discovery is based on paper silver spot trading in London and paper silver futures trading in New York. The whole charade is based on the premise of little to no real physical silver ever changing hands. If holders of paper silver were to demand delivery of physical silver, supply would quickly run out, which is exactly what is happening right now. Historically however, almost all paper silver transactions have been digitally cash settled without anyone ever seeing any silver.

As there is no central market place for the trading of physical silver, the price for physical silver has been inherited from the spot and futures paper markets with an added premium covering the costs for refining, minting, shipping, storage, insurance and retail. With the developments over the last few days of investors shifting away from paper silver and taking delivery of physical silver, the whole market construct for precious metals is changing.

Price Disconnect between Paper Silver Price and Physical Silver Price

Despite the 16.2% silver spot price increase from USD 25.58 a week ago to USD 29.72 at the time of writing, THE SPOT PRICE OF SILVER still does not reflect the demand and supply on the physical silver market.

Over the last few days, we have seen unprecedented demand for silver bars andsilver coins at BullionStar. We currently have about 25 customers buying silver from us for every 1 customer selling. Typically, this ratio is about 2-3 customers buying for every customer selling.

To be able to handle the demand pressure, we have had to introduce a minimum order amount of SGD 499 or equivalent in other currencies. Our team members are working around the clock to try to fulfil all orders that have been placed. Our order volume, call volume and email volume is up exponentially, around ten times to normal.

Furthermore, as the silver squeeze and shortage is getting more

serious by the hour, we do not expect to be able to replenish many

silver products anytime soon. As the spot price does not match the

demand on the physical market, we have had to significantly increase

price premiums for silver. (...)

Paper Silver Market Default/Failure – Moving to Fixed Prices

As more savers and investors take physical delivery of silver, we believe that there is a significant risk that some of the silver paper markets may default in that they are not able to deliver physical silver in exchange for the paper silver. Baring a full default, the paper price of silver may continue to inaccurately reflect the demand and supply of real physical silver.

With all supply of physical silver drying up at an incredible pace, it is becoming increasingly difficult for us to set prices and price premiums.

Unless the spot spot price of paper silver starts to reflect the real physical equilibrium price of silver, BullionStar may soon have no option but to abandon setting prices based on silver spot price altogether and move to fixed prices.

Worldwide Shipping of Bullion – Reduced Shipping Rates

With the WSB movement starting in the United States, we note that nearly all US bullion dealers seem to be completely sold out on physical silver.

(...)

Post in evidenza

The Great Taking - The Movie

David Webb exposes the system Central Bankers have in place to take everything from everyone Webb takes us on a 50-year journey of how the C...

-

VENICE and LEIBNIZ: The Battle for a Science of Economy By Michael Kirsch LaRouchePAC If citizens knew that between Isaac Newton, Rene...

-

Questo è Cefis. L’altra faccia dell’onorato presidente - di Giorgio Steimetz, Agenzia Milano Informazioni, 1972 01 Le due potenze occulte d...

-

Covered Bonds & Bank Paper Trading Fraud Nov 5, '08 4:02 PM for everyone Category: Other Covered Bonds & Bank Paper ...