Malaysia Files Criminal Fraud Charges Against Goldman Sachs

In

an unprecedented move that possibly foreshadows similar charges from

the US DOJ - and lots of headaches for the "recently retired" Lloyd

Blankfein - the Malaysian attorney general has filed criminal charges

against Goldman Sachs - targeting two of the investment bank's Asian

subsidiaries and two former Goldman bankers who have already been

charged by the US (former Southeast Asia head Tim Leissner and banker Roger Ng), accusing the investment bank of violating the country's securities laws by lying in bond agreements for three deals that raised $6.5 billion for 1MDB, a Malaysian

sovereign wealth fund formed under former Prime Minister Najib Razak

that US authorities believe was looted for upwards of $4 billion by

corrupt bankers and officials.

While authorities in Singapore, Switzerland and elsewhere had already filed criminal charges against various banks involved with the scandal last year, the first charges against Goldman and its employees over their involvement in the scandal materialized two months ago when the DOJ indicted Leissner and Ng.

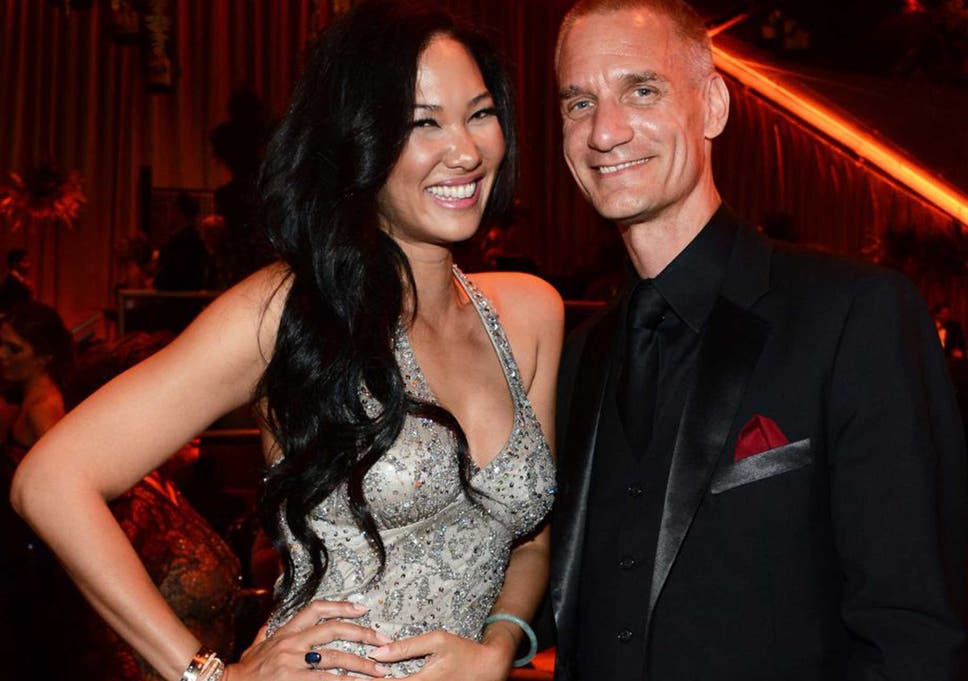

Shortly after the indictments, media reports revealed that senior Goldman executives - most notably, former CEO Lloyd Blankfein - were involved with the transactions. Blankfein attended at least three meetings with either Razak or disgraced Malaysian financier Jho Low, the allegedly corrupt financier who was also indicted by Malaysian authorities on Monday, even inviting Low to a private sit down at Goldman's 200 West Street headquarters. While pursuing the deal, Goldman employees - including Blankfein - brushed aside concerns raised by the bank's compliance department, and allowed Low to function as an unofficial intermediary between the bank and the Malaysian government, despite the bank's compliance department warning that Low was not to be trusted. The DOJ is also reportedly looking into the role of other senior Goldman bankers.

The charges followed reports over the weekend claiming that former senior Goldman employees believe 1MDB could tarnish Blankfein's legacy for reviving the bank's reputation following a massive 2010 settlement for abuses related to its sales of mortgage bonds before the financial crisis. Commenting on the 1MDB deals, one executive said "something doesn't smell right" and questioned how they managed to get past compliance.

Goldman executives who have so far evaded prosecution now have another reason to be anxious, because even if they avoid scrutiny by the DOJ, the US does have an extradition treaty with Malaysia.

This holiday season, 1MDB has truly become the gift that keeps on giving for Blankfein.

While authorities in Singapore, Switzerland and elsewhere had already filed criminal charges against various banks involved with the scandal last year, the first charges against Goldman and its employees over their involvement in the scandal materialized two months ago when the DOJ indicted Leissner and Ng.

Shortly after the indictments, media reports revealed that senior Goldman executives - most notably, former CEO Lloyd Blankfein - were involved with the transactions. Blankfein attended at least three meetings with either Razak or disgraced Malaysian financier Jho Low, the allegedly corrupt financier who was also indicted by Malaysian authorities on Monday, even inviting Low to a private sit down at Goldman's 200 West Street headquarters. While pursuing the deal, Goldman employees - including Blankfein - brushed aside concerns raised by the bank's compliance department, and allowed Low to function as an unofficial intermediary between the bank and the Malaysian government, despite the bank's compliance department warning that Low was not to be trusted. The DOJ is also reportedly looking into the role of other senior Goldman bankers.

The charges followed reports over the weekend claiming that former senior Goldman employees believe 1MDB could tarnish Blankfein's legacy for reviving the bank's reputation following a massive 2010 settlement for abuses related to its sales of mortgage bonds before the financial crisis. Commenting on the 1MDB deals, one executive said "something doesn't smell right" and questioned how they managed to get past compliance.

"We believe these charges are misdirected, will vigorously defend them and look forward to the opportunity to present our case. The firm continues to cooperate with all authorities investigating these matters," Goldman said in a statement to the Wall Street Journal.In a statement to the Financial Times, Tommy Thomas, Malaysia’s attorney-general, alleged in a statement that Goldman received $600 million in fees for its role, a total that was "several times higher than the prevailing market rates and industry norms." Malaysia is demanding that Goldman forfeit all of the fees it was paid by the Malaysian government (which were paid at a higher-than-market rate to reflect certain "risks" related to the deal), as well as additional punitive money. While the DOJ has alleged that some $4.5 billion was stolen from 1MDB, Malaysian authorities are targeting $2.7 billion.

"Malaysia considers the allegations in the charges against the accused to be grave violations of our securities laws, and to reflect their severity, prosecutors will seek criminal fines against the accused well in excess of the $2.7 billion misappropriated from the bonds proceeds and $600 million in fees received by Goldman Sachs, and custodial sentences against each of the individual accused: the maximum term of imprisonment being 10 years," the attorney general’s statement said.Malaysia's indictment alleged that statements in Goldman's bond-sale documents were "false and misleading," and that the Goldman employees who were involved personally profited and benefited from the deals.

Malaysia said the offering circulars and private placement memorandum issued by Goldman for the three bonds contained statements which were "false, misleading, or from which there were material omissions" because they said proceeds of the bonds would be used for legitimate purposes.Already the 1MDB controversy has inspired some Goldman clients to cut ties with the bank, particularly among the sovereign wealth fund set, which the bank had targeted as a "key growth area." One Abu Dhabi fund has sued Goldman over unspecified damages related to 1MDB.

"Offering circulars and private placement memorandum are serious documents, intended to be relied on, and, in fact, were relied on, by purchasers of the bonds," it said..

Malaysia said the accused structured the bond issues for “ostensibly legitimate purposes when they knew that the proceeds thereof would be misappropriated and fraudulently diverted”.

"In addition to personally receiving part of the misappropriated bond funds, those employees and directors of Goldman Sachs received large bonuses and enhanced career prospects at Goldman Sachs and in the investment banking industry generally," the attorney-general’s office alleged.

Goldman executives who have so far evaded prosecution now have another reason to be anxious, because even if they avoid scrutiny by the DOJ, the US does have an extradition treaty with Malaysia.

This holiday season, 1MDB has truly become the gift that keeps on giving for Blankfein.