Rushed Popular resolution casts long shadow over Europe's banks

At

8:33am on Monday June 5 2017, an email landed in a mailbox at Banco de

Espana. A bank run was underway at Banco Popular, one of Spain’s biggest

banks. Barely three minutes into the working week, the situation was

already critical – Popular was running out of cash, and fast.

The

email contained a formal request: Popular was appealing to the Spanish

central bank for €1.9bn in emergency liquidity assistance.

For

officials at Banco de Espana, the request was not unexpected. They had

been working for more than two months with a team from Popular to

prepare for this moment, ever since an internal audit at the lender had

uncovered financial irregularities totalling hundreds of millions of

euros at the end of March, irregularities that included a web of

Luxembourg companies designed to hide the extent of Popular’s bad loan

problem.

By 11:41am the same morning, the money was with Popular.

The injection came just in time – according to people involved, the bank

wouldn’t have survived another half an hour. But any relief was

short-lived. As deposits continued to pour out, it soon became clear the

bank would need more help. At 3:32pm, Banco de Espana received another

email from the bank, this time requesting an increase in ELA to €9.5bn.

WITHIN THE LIMITS

Although

high, the amount was within the limits previously discussed. Popular

had €40bn of unencumbered assets available, and Banco de Espana had

earlier indicated that €26bn of those would meet its secretive ELA

criteria. Once haircuts – of between 35% for the best assets and 90% for

the worst – were applied, officials calculated the central bank could

lend Popular just over €10bn, albeit at a penal interest rate of more

than 12%.

But, first, approval was needed from the European

Central Bank, which had to sign off on any ELA request greater than

€2bn. Despite it being a public holiday in Germany, the ECB governing

council discussed the matter by phone. Popular was confirmed as solvent,

and the request was approved. But what happened next came as a shock:

Banco de Espana turned down the request, citing incomplete paperwork.

Popular

staff worked through the night to meet the central bank’s last-minute

demands, which were threatening its access to vital ELA. The bank still

had €21bn of acceptable collateral left - €5bn had been used to secure

the first tranche of ELA - and these issues with the paperwork hadn’t

been flagged before. Banco de Espana eventually gave the green light to a

further €1.9bn the next day, but it was too little, too late.

“It

was embarrassing,” said one person involved. “In March we started

discussions – in March! We were doing trial runs, going back and forth

with the collateral. They had checked it. But the truth is they were

absolutely determined not to take it. By the time they realised they had

to, they just weren’t ready. We started hitting all these little

hiccups, and then suddenly they told us they couldn’t do anything more.”

Popular had €26bn of collateral, entitling it to €10bn of ELA

Source: Banco de Espana

The sudden denial of ELA has puzzled many since.

“Crucially,

the bank was still solvent,” said Jerome Legras, head of research at

Axiom, an asset manager that focuses on banks and owned a small amount

of Popular bonds. “They mostly had a cash problem. If it was possible to

lend €80bn of ELA to Greek banks to keep them afloat when they were

completely insolvent, then why couldn’t they do the same with Popular?

There is a real problem of consistency.”

By the end of the day on

Tuesday, Popular bosses concluded the bank simply could not open the

next day. They notified the ECB, which declared Popular – a bank it had

deemed solvent a day earlier – as “failing or likely to fail”. That

morning Popular become the first, and to date only, bank to be put into

resolution using new European rules brought in after the 2008 financial

crisis to make bank failures more orderly.

STRUCTURAL WEAKNESSES

The

mess around ELA is just one in a series of mishaps in the Popular case

that have raised questions about whether the system to deal with failing

banks is fit for purpose. Through dozens of interviews and a trove of

confidential documents totalling thousands of pages, IFR has pieced

together what happened during Popular’s final days. It is clear that,

despite the bank’s problems being flagged many months in advance, when

the crisis finally hit authorities found themselves ill-equipped and

ill-prepared to adequately deal with the situation.

Indeed, far

from being an orderly resolution, the Popular case has since become a

legal quagmire. European institutions including the ECB and Single

Resolution Authority, which was set up in 2015 specifically to plan for

and oversee the resolution of failing banks, are now defendants in more

than 100 legal cases. One common theme is that, despite plenty of

warning and years of preparation, the approach of authorities was

piecemeal and ad hoc.

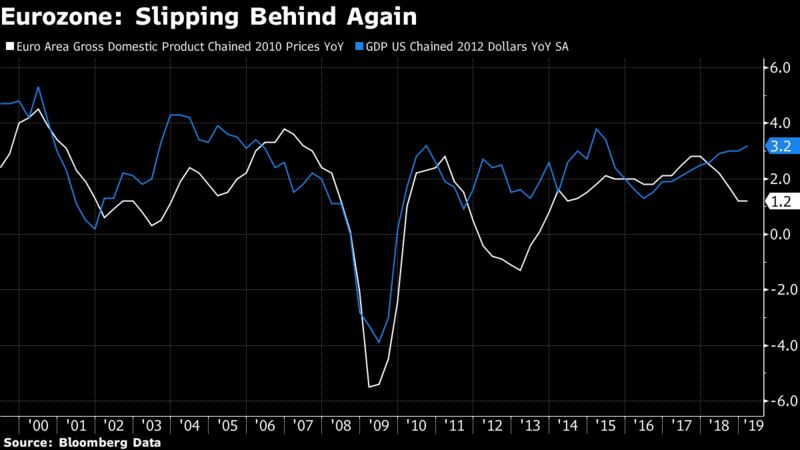

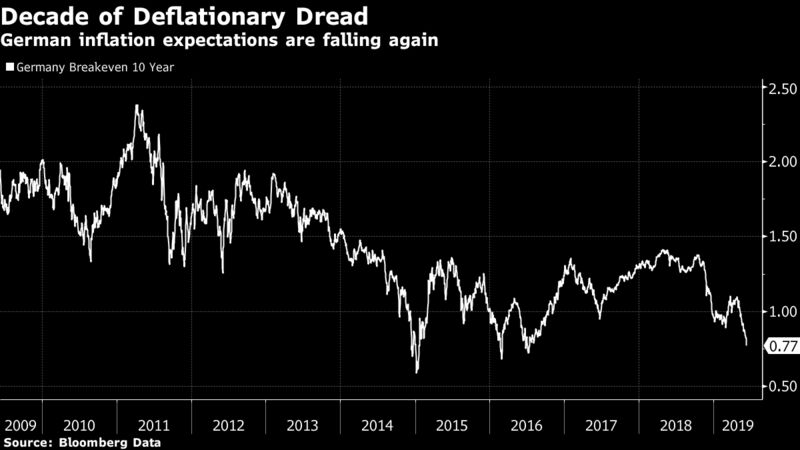

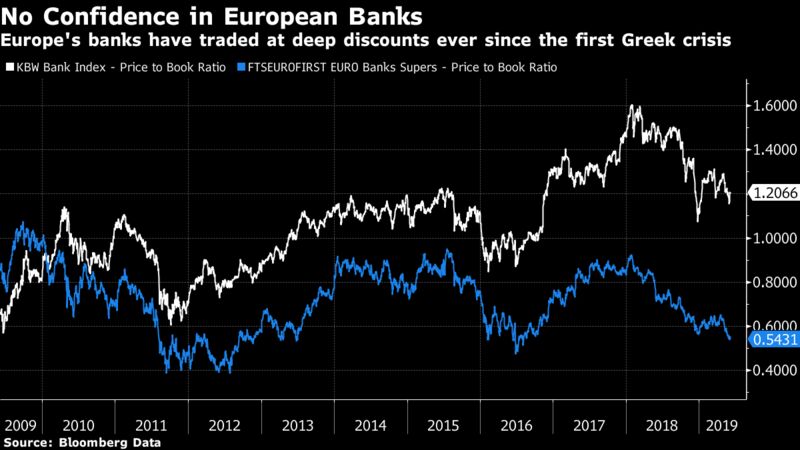

The issue goes much wider than just Banco

Popular; it has implications for the health of the entire European

banking system. Since the resolution of Popular, there has been a

dramatic increase in the cost of borrowing for even the healthiest of

banks. While a multitude of factors is doubtless in play, many believe

that the way the Spanish bank was dealt with is the biggest contributor.

Investors no longer trust that failing banks will be dealt with in an

orderly and legalistic way.

“It is absolutely critical that the

law is complied with,” said Richard East, a lawyer at Quinn Emanuel,

which is representing a group of disgruntled bondholders. “The SRB

cannot make up the rules as it goes along. The EU legislator took years

to design and lay down these rules in the wake of the financial crisis.

Investors cannot invest with confidence if they see that the regulator

is acting outside of its own rules.”

Former shareholders and

bondholders of the failed Spanish bank are leading the charge for

answers – and change. The two groups were hit hard: all shares were

annulled, while €2bn of bonds were bailed in then written down to zero.

The bank was then sold to Santander for a token €1. Investors argue that

the resolution process, overseen by the SRB, was flawed. They are

seeking billions of euros in compensation.

FLAWED VALUATION

Like

Banco de Espana, the SRB missed vital opportunities in the run-up to

Popular’s collapse that left it critically unprepared. It is clear that,

as early as April, the resolution body was so concerned about the

situation that, during a routine visit to visit Spanish banks in Madrid,

it thought it prudent to move its long-standing meeting with Popular

from the bank’s own offices to Banco de Espana, so as not to arouse any

suspicions.

During the meeting, Popular’s worsening liquidity

situation - more than €5bn of deposits would leave the bank that month -

was discussed. That should have been cause for concern, given that

almost all the SRB’s routine planning for a resolution of Popular had

revolved around potential solvency issues - not liquidity problems.

Despite that, the SRB critically saw no need to start a “special

dialogue” with the bank at that stage.

Perhaps one reason was

because the SRB knew it was seriously under-tooled to deal with a

liquidity crisis. Due to a slow phase-in of funding for the resolution

agency, and despite having been set up more than two years previously,

the SRB had only €10bn of funds to fight a crisis, less than a quarter

of its planned firepower. Internal rules also severely limited how those

funds could be used.

“This was the first case in our history and

all the elements were not in place,” said one person involved with the

resolution process. “We built our strategy on the bail-in tool. But due

to the characteristics of the crisis, it would have been difficult to

implement. And we were not sure that all the tools would have been

available from a liquidity perspective. At that moment, the available

amount was limited.”

The person said that the SRB quickly realised

that only one of the potential options in its resolution toolbox was

really available: a sale of Popular to a healthier bank that could

inject liquidity. Even then, it waited until May 23 to begin any serious

work, when it commissioned Deloitte to put together a detailed

valuation of Popular, which would inform any future sale of the bank.

HIGHLY UNCERTAIN

On

May 28 the SRB ordered Deloitte to “strictly prioritise … focusing only

on key assets and liabilities where there is considerable valuation

uncertainty”. Three days later it called to say it that the accountancy

firm had only two more days to complete its work.

As a result of

the compressed timeline, when Deloitte completed the report, it warned

that its findings were “highly uncertain”. It further prefaced its work

with the warning that it had “not had access to certain critical

information”. Reflecting this uncertainty, Deloitte’s report estimated

Popular could be worth as much as €1.8bn in a best case, a negative €8bn

in a worst case and a negative €2bn in a “best estimate” scenario.

Deloitte letter to Single Resolution Board

Source: Single Resolution Board

Despite

the caveats, the negative €2bn number formed the basis for the sale of

the bank and tallies exactly with the losses later imposed on

bondholders.

On June 3, while Popular and Banco de Espana were

doing final checks on the doomed ELA process, resolution authorities

made contact with Santander and BBVA, piggybacking on a failed sales

process (that involved five interested parties) Popular had run earlier

in May. After signing non-disclosure agreements the next day, the two

spent Monday and Tuesday going over Popular’s books. When Popular was

declared “failing or likely to fail” on Tuesday evening, both were

invited to submit binding offers.

Only one bid arrived: from

Santander, for €1, but only on the condition that shareholders, AT1

holders and Tier 2 holders were bailed in.

UPPER HAND

With

insufficient liquidity of its own to support Popular, and having already

concluded that a winding up of the bank under normal insolvency

proceeding would pose risks to financial stability, the SRB was left

with little option but to accept the offer. Reports in the Spanish press

allege that Santander’s own lawyers took the purchase agreement drawn

up by resolution authorities and rewrote it.

“The auction was

organised so quickly that it was difficult for anyone to make a serious

offer, and the valuations they used to justify the sales price were also

difficult to understand,” said Axiom’s Legras. “The range was enormous

and the methodology looked more like doing a firesale on the entire

balance sheet. With that sort of approach, any bank, even the most solid

one, will look very weak.”

Critically, investors allege that the

situation clearly compromised the SRB and its obligation to ensure that

shareholders and bondholders were dealt with fairly. Santander had been

given access to Popular’s financials as part of the private sales

process for weeks, and internal presentations show it had considered

paying up to €1.6bn for Popular just a few weeks before, but it held off

on making an offer.

One

person involved in that failed sales process said that because Popular

was suddenly no longer working with its own advisers to arrange a deal,

Santander held all the cards.

“Suddenly you change your

counterparty from professional M&A bankers, with a whole structure

of corporate governance and a board and shareholders to convince, to

civil servants of something called the resolution authority who have

never ever done anything like this,” said the person.

“These civil

servants, who barely have the capabilities to understand how a bank is

valued, are called in during the very last days with a mission – a

mission impossible – to dispose of assets according to rules that were

thought up years before and completely detached from the reality of the

way things work and the speed at which things happen. Santander must

have thought, ‘we have a great negotiating hand here’.”

INVESTOR PROTECTIONS

European

lawmakers at least foresaw the possibility of a rushed resolution, and

within the rules governing the SRB is a requirement to conduct an

“independent” valuation of a bank after the event to determine whether

or not shareholders and bondholders were short-changed, and whether they

might have seen a better outcome in an insolvency. If so, compensation

is due.

While the SRB says such an assessment was made, investors

believe it was not “independent”. Deloitte, the same firm that did the

first assessment, was asked to do it, which investors say is a clear

conflict of interest. The second Deloitte report concluded that

shareholder and bondholder losses would have been much greater under a

normal insolvency process.

“This is the safety valve of the entire

regime,” said East, the lawyer at Quinn Emanuel. “The SRB is simply

making things up as it goes along; it doesn’t really seem to know what

it is doing.”

“Unless there is serious and thorough review of the

Banco Popular case by the EU General Court, no lessons will be learned,”

he said. “This is our only hope because the SRB has vigorously denied

shareholders and bondholders access to documents and data for the last

two years … and will not admit that anything it did was wrong.”

The risk of botched resolutions will remain as long as the current regime remains in place, others believe.

“The

process gives so much leeway and flexibility to authorities that they

pretty much can do anything they want,” said Legras. “And the result is

that you can end up with something that is fairly reasonable and well

managed – or the exact opposite. There are very few safeguards for

investors and stakeholders. It’s an open bar for the authorities.”