Dishonourable Debt: Why Borrowers Are Not Legally Bound To Repay Bank Loans

I intend to do what

little one man can do to awaken the public conscience, and in the

meantime I am not frightened by your menaces. I am not a giant

physically; I shrink from pain and filth and vermin and foul air, like

any other man of refinement; also, I freely admit, when I see a line of a

hundred policemen with drawn revolvers flung across a street to keep

anyone from coming onto private property to hear my feeble voice, I am

somewhat disturbed in my nerves. But I have a conscience and a religious

faith, and I know that our liberties were not won without suffering,

and may be lost again through our cowardice. I intend to do my duty to

my country.1

— Upton Sinclair, Letter to the L.A. Chief of Police, 17 May 1923

A classic proverb holds that “there is honour among thieves”.

For 99% of thieves, this proverb is actually true.

But there is a minority of thieves, alas, who have no honour at all. They are the thieves who create 97% of our money—in the form of debt—through the magic of double-entry accounting.

Thanks to the added magic of compounding

interest owed on all the money, the total amount of debt owed worldwide

has grown so large, it is now impossible to repay. Although, truth be

told, because all of the ‘money’ is actually debt, it has

always been impossible to repay, because repaying all the debt would

eliminate all the ‘money’.

As two authorities on the matter—one, the High Priest, the other, a mere deacon of the Federal Reserve Bank—intoned way back in the Great Depression:

If there were no debts in our money system, there wouldn’t be any money.2

If all the bank loans

were paid up, no one would have a bank deposit, and there would not be a

dollar of currency or coin in circulation. This is a staggering

thought. We are completely dependent on the commercial banks for our

money. Someone has to borrow every dollar we have in circulation, cash

or credit. If the banks create ample synthetic money, we are

prosperous; if not, we starve. We are absolutely without a permanent

money system. When one gets a complete grasp upon the picture, the

tragic absurdity of our hopeless position is almost incredible – but

there it is. It is the most important subject intelligent persons can

investigate and reflect upon. It is so important that our present

civilization may collapse unless it is widely understood and the defects

remedied very soon.3

If you were not previously familiar with

the illogical, paradoxical, circular pseudo-realities that arise from

double-entry accounting, then Welcome to Numberland, Alice.

Even though this is the objective truth,

the irrefutable reality of how the debt-based ‘money’ system works, most

of us continue to believe in the impossible.

That is to say, we continue to believe—falsely—that we are bound to honour our debts.

Famed anthropologist and author of Debt: The First 5000 Years, David Graeber explains:

That common-sensical

notion not only that it’s moral to pay one’s debt, but also that

morality essentially is a matter of paying one’s debts can bring people

to justify things that they would never think to justify in any other

circumstance.4

Economist and historian Michael Hudson

says that the bankers have known about this anthropological discovery

since at least the 1980’s:

They found out that the

poor are honest. Almost the only people who believe they should repay

their debts are the poor people. And in fact, the less money you have,

the more you believe the debts should be paid.5

Nearly 2500 years ago, the man widely

acknowledged to be the foundational figure for Western science,

philosophy, law-making, and mathematics, gave this instruction to

lenders and borrowers:

μηδὲ νόμισμα

παρακατατίθεσθαι ὅτῳ μή τις πιστεύει, μηδὲ δανείζειν ἐπὶ τόκῳ, ὡς ἐξὸν

μὴ ἀποδιδόναι τὸ παράπαν τῷ δανεισαμένῳ μήτε τόκον μήτε κεφάλαιον

No one shall deposit

money with anyone he does not trust, nor lend at interest, since it is

permissible for the borrower to refuse entirely to pay back either

interest or principal.6

It turns out that Plato was right.

It is permissible—legally—for all the world’s borrowers to refuse to honour all their debts to all the world’s banks.

The reason why is because—legally—no bank has lent us any money.

In fact—according to the banks themselves—legally, all the money in the banks was lent by us to them.

(Feeling dizzy Alice?)

According to Black’s, the most widely used law dictionary in the United States7, “money” is legally defined as (emphasis added):

A general, indefinite

term for the measure and representative of value; currency; the

circulating medium; cash. “Money” is a generic term, and embraces every

description of coin or bank-notes recognized by common

consent as a representative of value in effecting exchanges of property

or payment of debts. Hopson v. Fountain. 5 Humph. (Tenn.) 140. Money is

used in a specific and also in a general and more comprehensive sense.

In its specific sense, it means what is coined or stamped by public authority, and has its determinate value fixed by governments. In its more comprehensive and general sense, it means wealth.8

Rather than lending us legal money, bankers have misled and deceived us into renting a record of a promise to pay legal money.

They have misled and deceived us into believing that their record of their promise to pay us money, is actually money (legal substance).

They have also misled and deceived us into believing that their record of their promise to pay us money, is actually our money (ownership title).

And here’s the real kicker.

Despite the fact that they claim to have

loaned us all this money, thanks to the magical paradox at the heart of

double-entry accounting, they also claim, simultaneously, precisely the opposite to be true — that we have actually loaned all that money to them.

(We will return to this later – think “bail-in”).

It really does beg the question, “Does anyone really own money?”

Because the ‘money’ that the bankers have purportedly ‘loaned’ to us—that we have loaned to them—is

neither money in true legal substance, nor is it certain just whose

‘money’ it actually is, we can confidently assert that the bankers have

- misrepresented the sign, true substance, and true value of the “consideration” component of the loan agreement,

- engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in the withholding and/or obfuscation of key information pertaining to their capacity to deliver on their promise of performance,

- made false, misleading, and deceptive statements and representations in the inducement of borrowers to enter into an agreement of exchange of mutual performances (the “offer”),

- failed to deliver on their promise of performance (“failure of consideration”),

- engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in obfuscating their failure to deliver on their promise of performance, and

- gained dishonest advantage (“interest”, “yield”, “return”) through these acts of misleading and deceptive conduct.

You may well be feeling—like Alice—rather

incredulous about this, and questioning how it is possible. After all,

surely the financial accounting standard-setters and our government

regulators would prevent such things from happening?

Alas, no.

Just as with double-entry accounting—the magical foundation on which the entire parasite worm-ridden edifice of global banking and finance is built—the truth is exactly the opposite.

Ever since the “financial reporting revolution ushered in by financial economics ascendance in the 1960s”9

and the “increasing hegemony of neo-liberal ideology over issues of

public policy and regulation ushered in by Reagan and Thatcher”10, the financial accounting standards bodies and government regulators have aided and abetted the bankers in their misleading and deceptive conduct:

Well documented is the

growing dominance of the social sciences and of business education by

neoclassical economic ideas (Ferraro, Pfeffer, & Sutton, 2005),

which form the intellectual foundation of neo-liberal morality and

politics.11

Transforming accounting

in the academy into a neoclassical economics sub-discipline (Reiter

& Williams, 2002), which the financial reporting revolution

accomplished, has impoverished accounting discourse as a moral discourse

(Reiter, 1998; Williams, 2000) and led to the understanding of

accounting as a practice whose purpose is to cohere with a world made

natural by the discourse of neoclassical economics.12

For at least four decades, the private

not-for-profit (oh really?) financial accounting standard-setters (FASB,

IASB) have continued to actively aid and abet the bankers’ misleading

and deceptive conduct, despite frequent accounting-enabled corporate

scandals and resultant financial crises, and the often stunning

revelations and criticisms presented in the peer-reviewed accounting

literature (emphasis added):

The savings and loan

failures in the late 1980s and 1990s, the Enron, Global Crossing and

Tyco corporate scandals, Andersen’s demise, and the sub-prime mortgage

crisis all relate to deception [emphasis in original]. All such scandals involved to varying degrees the telling of accounting untruths…13

Accounting representations are true if they predict, or true if they abet the privileged group to pursue its objectives, a quite different notion of true than implied by the popular usage…14

[M]any accounting signs no longer refer to real objects and events and accounting no longer functions according to the logic of transparent representation, stewardship or information economics.15

[A]ccounting today no longer refers to any objective reality but instead circulates in a “hyperreality” of self-referential models.16

The accounting sign now precedes (and even creates

through its ‘‘sign value’’) the referent that it once purported to

represent. It is no longer an abstraction or an appearance of any

‘‘real’’ thing. It is its own pure simulation, making circular

references to other models which themselves make circular references to

accounting signs.17

Are such disasters

[Enron] necessary before accountants begin to realise how indispensable

it is to make a distinction between conceptual representation (including

accounting representations and misrepresentations) and the reality to be represented?18

As mentioned earlier, around 97% of so-called ‘money’ in ‘circulation’ (hint: it doesn’t actually circulate

in the true meaning of the word; it magically disappears in one place,

and magically reappears in another) is not actually money (“coined or stamped by public authority”)19. It is bank-created ‘credit’.

By legal definition, bank ‘credit’ is not real money.

Bank ‘credit’ is actually just an electronic double-entry accounting record of the bank’s promise to pay real money.

However, this objective legal reality has

not prevented the FASB/IASB from aiding and abetting the bankers in

their false, misleading and deceptive misrepresentation of the mere sign of money as actually being real legal money, and consequently inducing prospective borrowers into forming loan agreements for the purpose of gain for the bankers (“interest”, “yield”, “return”) on the basis of this fundamental misrepresentation.

For example, effective July 1, 2009—that

is, in the middle of the global banking liquidity crisis known as the

“GFC”—the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) introduced

Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) §305 Cash and Cash Equivalents. This new standard effectively sanctioned—and obfuscated—the banks’ misleading and deceptive conduct in renting records of promises to pay under the guise of so-called ‘money’ (emphasis added; duplicitous weasel words underlined):

Cash

Consistent with common usage, cash includes not only

currency on hand but demand deposits with banks or other financial

institutions. Cash also includes other kinds of accounts that have the general characteristics of demand deposits in that the customer may deposit additional funds at any time and also effectively may withdraw funds at any time without prior notice or penalty. All charges and credits to those accounts are cash receipts or payments to both the entity owning the account and the bank holding it. For example, a bank’s granting of a loan by crediting the proceeds to a customer’s demand deposit account is a cash payment by the bank and a cash receipt of the customer when the entry is made.

This codification of the bookkeeping entry record of bank ‘credits’—the record of a promise to pay cash—as actually being (“is“) ‘cash’, is in clear contradiction of the legal definition of money.

An electronic record of a promise to pay cash

- is not “coin or bank-notes”,

- is not “coined or stamped by public authority”,

- is not “currency” or “cash”; that is to say, not in any sense that is or would be “recognized by common consent“ (Black’s) as being actual “currency” or “cash” (i.e., coin or bank-notes; legal tender).

According to the International Institute

of Certified Public Accountants (IICPA) in an Open Letter to both the

FASB and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) in May

2013, this codification of banks’ electronic ‘credits’ as (not representing but) actually being

“cash” is also in breach of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

(GAAP) and the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS);

(emphasis added):

Demand deposits

referred to by the public as “cash in bank” is recorded and reported by

monetary financial institutions (MFI) in units of account by

double-entry bookkeeping in a process which the MFIs call “lending” —

but which is effectively a nullity — by debiting loans receivable and

crediting demand deposits.

These so created units

of account are then denominated at will in dollars, pound sterling,

euros, etc., depending on the terms of the documentation or underlying

promissory note, or whatever is the legal document giving rise to this

type of “lending,” using whatever is the name of the currency in the

jurisdiction in which it takes place, but legal tender the “demand deposits” are not.

These so-called “loans receivable” that give rise to these so-called “demand deposits”

- are not assets within the meaning of economic resources,

- do not have the capacity to eventually result in cash inflows (cash being legal tender or central bank money, so called federal funds),

- are created bank-internally and therefore in violation of self-dealing,

- have no cost basis,

- have no market value except by way of assignment against like-kind-nullities to or from other MFIs never settled in legal tender or central bank money.20

If that were not enough, it gets worse.

Astonishingly, the FASB’s ASC §305-10-55-1 Implementation guidance tumbles even further down the rabbit hole of logical and legal unreality—not to mention amorality—in stating what the bank customers’ perspective of so-called “Cash and Cash Equivalents” “shall” be (emphasis added):

Cash on deposit at a financial institution shall be considered by the depositor as cash rather than as an amount owed to the depositor.

This codification by an unelected,

private not-for-profit financial accounting standards organisation of

how the general public “shall” consider their so-called “cash on

deposit”, is in clear contradiction of

- the legal definition of “money”,

- the common understanding of the word “cash” as meaning a government-created tangible entity (i.e., legal tender notes and coins),

- the banks’ own balance sheet records affirming all customer “deposits” as being a Liability (i.e., amounts owed to customers),

- the banks’ perspective regarding ownership title (claim) on this so-called “cash” (a perspective backed, incidentally, by the Financial Stability Board in its G20-wide “resolution regime” in preparation for “bad” bank bail-ins).

The FASB has ex post facto codified that banks may consider bank ‘credits’ (a record of a promise to pay cash) as actually being “cash” for accounting purposes; that the customers’ perspective of bank ‘credits’ “shall” be that those ‘credits’ are (literal physical) “cash”, and, that they are not

amounts owed to them by the bank, wholly irrespective of whether or not

the banks have actually met (or will actually meet) their legal

obligations under contract law.

While the FASB might imagine that it can—without any practical or legal implications—surreptitiously

decree how hundreds of millions of “depositors” “shall” view their

“deposit”, the truth of the matter is that an immediate contradiction,

and critical conflict of interests arises.

Quite simply, the FASB’s ASC §305 Cash and Cash Equivalents

codification does not even comply with the rules of double-entry

bookkeeping, much less the common understanding of the true meaning of

the word “cash”. It has potentially far-reaching implications for the

legal standing of banks’ claims on borrowers for the (re)payment of

“consideration” (plus compounding “interest” in addition), in that it

serves to highlight the false, misleading, and deceptive statements and

representations of banks in the formation of loan contracts.

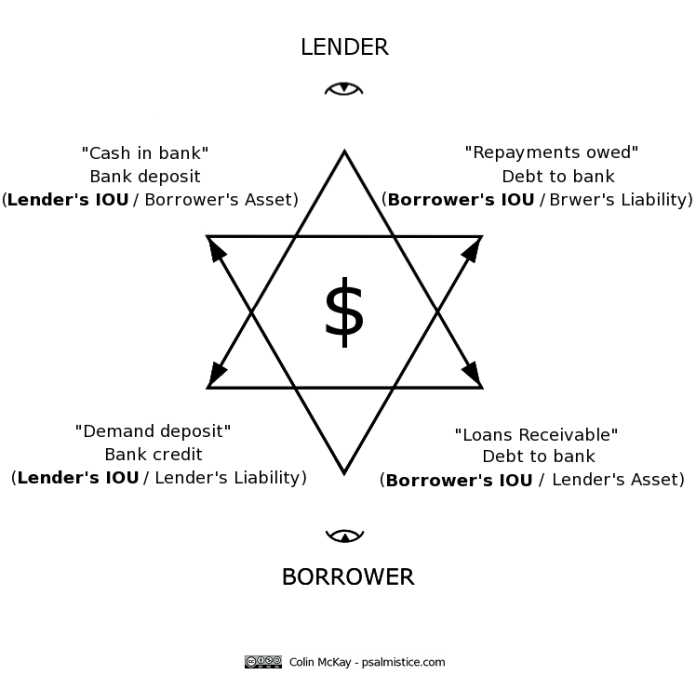

To illustrate this critical point, the following diagram depicts all of the perspectives (views), concepts, and realities

that are inherent in a double-entry bookkeeping-based ‘account’ of the

bank Lender – customer Borrower relationship. Keeping in mind that—since

the time of the Stoics—it has been considered an “indispensable”

fundamental of philosophical and scientific discourse to express clearly

the difference and relation between the threefold notions of the sign (sound, written symbol, etc), the conceptual idea (meaning) communicated by the sign, and the real (the actual object or event behind the concept)21, all three notions — “Sign”, Concept, (Real) — are clearly marked for each party and each perspective of the two-sided, legally-binding mutual “exchange” of promises-to-pay.

Consider carefully the following:

- Irrespective of whether one adopts the perspective of the Borrower or the Lender, any so-called “cash” or “demand deposit” appears only as a sign (sound, name, symbol, i.e., a mis–representation) of the Lender’s IOU,

- The real object or event underlying the purported existence of “cash in bank” (or “demand deposit”), is the Lender’s IOU (promise-to-pay); in other words, the real object or event is the Lender’s promise of performance (“consideration”), and not “coin or bank-notes” “stamped by public authority”,

- The sign (“cash in bank”, “money”, “funds”, “$”, “€”, “£”, etc) that is purported to the Borrower by the Lender to not merely represent but to actually be the underlying reality, is false, misleading, and deceptive,

- As the Borrower has been induced to accept the offer to contract with the Lender on the basis of false, misleading, and deceptive representations, the loan contract is unenforceable,

- The Lender’s IOU is simultaneously an Asset of the Borrower, and a Liability of the Lender (contradicting §305-10-55-1),

- As a loan agreement requires inter alia the exchange of mutual performances, and the Lender’s obligation is defined as necessarily preceding that of the Borrower, the recording and reporting of the Lender’s IOU as a Liability demonstrates that the Lender has failed to deliver on its promise of performance (“consideration”), i.e., to provide the Borrower with money (“coin or bank-notes” “stamped by public authority”); therefore, the loan contract is unenforceable.

There is one final matter to consider.

Since early 2009, the unelected Financial

Stability Board (FSB)—perennially chaired by Goldman Sachs alumni—has

been working with G20 governments and financial regulatory authorities

to implement a global banking “resolution regime”. One of the Key Attributes of this scheme is the passage of legislation granting governments the power to “bail-in” the “deposits” of bank customers in order to save or reestablish a “bad” bank or “systemically-important” financial institution.

Despite the reality that all so-called “customer deposits” have in fact been created ex nihilo by the banks through the act of “lending” to customers, and are reported as a Liability of the banks on their balance sheets (i.e., as ‘money’ still owed to

the customer), both the banks and the FSB’s global banking resolution

regime consider the customer to be a “creditor” of the bank.

In other words, rather than the bank having purportedly loaned (but not yet delivered) ‘money’ to the customer, the bank and the FSB deem that the situation is precisely the reverse – the customer has purportedly loaned his/her ‘money’ to the bank (note the implicit assumption of customer ownership).

Believe it or not, there is an

explanation—albeit a perverse, morally abhorrent and unconscionable

explanation—for this, and in turn, for how the creeping global preparations to legally

steal the “deposit” assets of bank customers (refer above diagram) is

able to be “justified” by the banks, the financial and political

authorities, and the unelected, BIS-funded, Goldman Sachs alumni-chaired

FSB.

At the heart of the matter is the ever-present paradox of perspective inherent in the Babylonian Duality Principle on which double-entry accounting is based.

Banks are able to create new (so-called) ‘money’ ex nihilo

through the loan origination process. As this is recorded using

double-entry accounting, every new loan results in a new Asset and a new

Liability on the banks’ balance sheet records.

However, because banks act both as new loan (thus, new ‘money’) originators and

as financial intermediaries, there is no way of disaggregating the

Liability side of any bank’s balance sheet in order to clearly

distinguish between those “deposits” that have arisen in consequence of

that bank’s own lending (so-called), and those “deposits” that

have arisen in consequence of that bank’s intermediation (i.e.,

‘transfers’ of ‘money’ from one customer account to another customer

account at the same bank, or, from the customer accounts of other financial institutions to customers of the bank).

Whether or not any particular unit of any particular “deposit” amount could truthfully be defined as ‘money’ loaned to the bank by a customer, or, loaned by the bank to a customer, is dependent on knowing with complete certainty how and when

each and every unit came to be recorded in the customer account. The

only customer account for which such certainty is possible, is a

customer account created by the bank at the moment of first originating a

loan, and, before any new entry for even one single fractional

unit of the denominated currency has been either added to, or

subtracted from that customer account.

There is one further exception – an

account established for one of the bankers’ favourite clients—arms

dealers, drug cartels, mafioso, and other criminal organisations such as

the CIA—at the first moment of the client handing over real legal

tender cash notes at the bank to open the account.

In any event, since even a ‘transfer’ of

‘money’ from one bank to another still has the same ultimate origin—an

out-of-nothing creation of an electronic record of a mutual exchange of

promises to pay—then from a whole-of-banking-system perspective it

really doesn’t matter; all so-called ‘money’ on ‘deposit’ is simultaneously owned by the customers, and by the banks.

(Oh yes, by the way, since that ‘money’

is really just a record of a promise, and we all buy and sell mostly by

way of ‘transfers’ entered in these electronic records, then, strictly

speaking, we are all thieves, because none of us is actually

giving real legal money in payment to our fellows in exchange for their

goods and services, unless we actually “cash-in” the bank’s “offer”

(promise) to pay us real money, in order to pay our fellow in real legal

money – government-created legal tender cash notes and coins).

The bankers—aided and abetted by the FASB, FSB et al—resolve this ownership contradiction by choosing

to have their cake and eat it too. That is to say, the bankers take

advantage of the embedded paradox of perspective in double-entry

accounting, and arbitrarily decide who will be deemed the true owner of

any and all “deposits” (i.e., who is debtor and who is creditor), depending—of course—on what suits the bankers’ best interests at any given moment in time.

In good times, it’s business as usual — the bankers will consider your “deposit” account to represent ‘money’ owned by and owed to you, and will—if they can—honour

their promise to give you real legal cash on demand (but will far more

commonly just ‘transfer’ your ‘credits’ to someone else’s account).

In not so good times, the bankers will

consider your “deposit” account to represent a loan from you to the bank

… and so, as you are now just an “unsecured creditor”, what you thought

was your ‘money’ in the bank can (and will) be legally purloined, to “bail-in” the “bad” bankers.

One might well ask why it is that the

generally “unsophisticated” (i.e., misled and deceived) customers of

banks should be made to suffer any loss or damage arising from a “bad”

financial institution’s employees or executives’ malfeasance,

misfeasance, or nonfeasance, and/or from their failure to use

record-keeping systems and methods adequate to the task of clearly

distinguishing between bank assets, and customer assets.

The answer lies (pun intended) in a

relatively recent accounting concept advanced by the standard-setters,

in consequence of the neoclassical / neo-liberal ideological takeover of

economics, accounting, and financial reporting. This wonderfully

Orwellian idea is called “decision usefulness” (emphasis added):

For standard-setters

the overriding criterion of decision usefulness, which FASB and IASB

narrowly define as helping to predict cash flows, has replaced veracity

in financial reporting as an end in itself. The ascension of decision

usefulness as a public rationale for FASB actions has produced for the

profession the situation .. [of] .. simultaneous committing to two, often conflicting ideas of truth…22

Decision usefulness has been and continues to be applied in accounting to justify

its activities, a singular emphasis on an accounting discourse which we

view as highly problematic and seriously impairing accounting as an

ethical practice.23

Truth poses a genuine problem for accounting, one that cannot be so easily finessed by appeals to decision usefulness.24

[A]ccounting standard

setters have replaced a responsibility for truth with decision

usefulness, which, given the ambiguity of decision usefulness,

effectively absolves them of responsibility for the consequences of their actions.25

In his recently released book The End of Alchemy, former governor of the Bank of England Mervyn King makes a similar observation (emphasis added):

“Regulation has become

extraordinarily complex, and in ways that do not go to the heart of the

problem. … Much of the complexity reflects pressure from financial

firms. By encouraging a culture in which compliance with detailed

regulation is a defense against a charge of wrongdoing, bankers and regulators have colluded in a self-defeating spiral of complexity.”26

Upton Sinclair famously said that “It is

difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends

on his not understanding it”.

Indeed, there are many who will doubtless object to the argument here presented—that it is legally permissible for all the world’s borrowers to refuse to honour all their debts to all the world’s banks—with a reflexive, ill-considered, tediously shallow and laughably ironic dismissal that “this is all just semantics”.

Quite so.

Semantics (from Ancient Greek: σημαντικός sēmantikós, “significant”) is the study of meaning. It focuses on the relationship between signifiers—like words, phrases, signs, and symbols—and what they stand for, their denotation.27

The entire matter pivots on the question

of truth. More specifically, the legal argument pivots on demonstrating

that there has been a mis-representation of the truth, by the bankers.

What is the true reality, the real object or event that has been promised to the borrowers by the bankers—that is to say, what is the true object or event as commonly understood by the borrowers—and

re-presented to the borrowers by the bankers using the signifiers

‘money’, ‘cash’, ‘funds’, ‘credit’, ‘deposit’, ‘sum’, ‘amount’, ‘$’, ‘€‘, ‘£‘, etc?

Has there, or has there not, been any false, misleading, or deceptive statements or representations made by the bankers to the borrowers, in order to induce the borrowers to agree to accept the offer to contract?

Have the bankers made any false, misleading, or deceptive statements or representations to the borrowers, that obfuscate a failure, potential failure, potential unwillingness, reasonably foreseeable or known incapacity of the bankers to deliver on their promise of performance?

And finally, have the bankers gained any

advantage (“interest”, “yield”, “return”) from the borrowers through the

use of false, misleading, or deceptive statements or representations?

May God grant the reader wisdom, and a sound conscience, to carefully and prayerfully judge the matter for themselves.

********

Regina: This isn’t your pixie dust is it.

Green: Well when you think about it does anyone really own pixie dust?

Regina: The fairies are quite proprietary about it. If they found out you stole it they would…

Green: Don’t worry about me. This is about you.

Green: Well when you think about it does anyone really own pixie dust?

Regina: The fairies are quite proprietary about it. If they found out you stole it they would…

Green: Don’t worry about me. This is about you.

– Once Upon A Time

********

DISCLAIMER: This essay

is the opinion of the author. Nothing stated or implied in this essay

should be construed to be legal or professional advice. For questions

concerning your specific situation, please consult a qualified legal

advisor.

********[1] Upton Sinclair, Wikiquotes, https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Upton_Sinclair , 8 May 2016

[2] Mariner S. Eccles, Chairman of the Federal Reserve, testimony to the House Committee on Banking and Currency, September 30, 1941, cited by G. Edward Griffin, The Creature From Jekyll Island (Third Edition, 1998), p. 188.

[3] Robert H. Hemphill, Credit Manager of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, foreword to Irving Fisher 100% Money (New York: Adelphi, 1936) p. xxii, cited by G. Edward Griffin, The Creature From Jekyll Island (Third Edition, 1998), p. 188.

[4] David Graeber, What We Owe to Each Other, interview in Boston Review, February 15, 2012

[5] Michael Hudson, In Debt We Trust: America Before the Bubble Bursts, Media Education Foundation transcript (pdf), 2006

[6] Plato, Laws, Book V; Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vols. 10 & 11 translated by R.G. Bury. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1967 & 1968.

[7] Black’s Law Dictionary, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black’s_Law_Dictionary, 4 May 2016

[8] What is Money?, Law Dictionary, http://thelawdictionary.org/money/, 4 May 2016

[9] Mohamed E. Bayou, Alan Reinstein, Paul F. Williams, To tell the truth: A discussion of issues concerning truth and ethics in accounting, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Volume 36 (2011), 109-124

[10] ibid.

[11] ibid.

[12] ibid.

[13] ibid.

[14] ibid.

[15] ibid.

[16] Norman B. Macintosh, Teri Shearer, Daniel B. Thornton, Michael Welker, Accounting as simulacrum and hyperreality: perspectives on income and capital; Accounting, Organizations and Society, Volume 25, Issue 1 (2000), 13-50

[17] ibid.

[18] Richard Mattessich, Accounting representation and the onion model of reality: a comparison with Baudrillard’s orders of simulacra and his hyperreality; Accounting, Organizations and Society 28 (2003) 443–470

[19] Positive Money, How Banks Create Money, http://positivemoney.org/how-money-works/how-banks-create-money/, 4 May, 2016

[20] Michael Schemmann (IICPA), Accounting Perversion in Bank Financial Statements — Demand Deposits Do NOT comply with IFRS (GAAP), 1 May 2013

[21] Richard Mattessich, Accounting representation and the onion model of reality: a comparison with Baudrillard’s orders of simulacra and his hyperreality; Accounting, Organizations and Society 28 (2003) p. 450-451, n. 12

[22] Mohamed E. Bayou, Alan Reinstein, Paul F. Williams, To tell the truth: A discussion of issues concerning truth and ethics in accounting, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Volume 36 (2011), 109-124

[23] ibid.

[24] ibid.

[25] ibid.

[26] Mervyn King, The End of Alchemy, quoted in Bloomberg, The Book That Will Save Banking From Itself, 5 May 2016.

[27] Semantics, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semantics, 8 May 2016

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento